On The Trail of Irish Revolution In Dublin

As a political junkie, I have always been fascinated by the Irish distinct national identity. Since Ireland is one of the wealthiest countries in the world, I had a hard time imagining the country was once the most rebellious corner of Europe just a hundred years ago. Ireland has the unique distinction of being the only member of the European Union that was once a full-fledged colony. Ireland’s political history is the story of heartbreak and resiliency. Since there was never a unified “Kingdom of Ireland,” Irish nationalism and the path toward freedom are filled with plenty of asterisks and complexity.

Cork may be called a “rebel city,” but the most momentous events occurred in Dublin. Historically, the Irish capital is the most “English” part of Ireland, even more so than Ulster. That may seem odd today, but it was not that surprising. As the capital, Dublin is home to Ireland’s political elites and merchant class, which benefitted the most from Britain’s imperial system. Many of Dublin’s most celebrated landmarks, such as Dublin Castle, were symbols of Britain’s colonial rule. Celebrated Irish institutions, like Trinity College, were exclusively reserved for English protestants.

A significant inflection point was the Act of Union when the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland officially integrated as a single political entity. The Irish parliament was dissolved, and all the Irish MPs moved to Westminster in London. The last shred of Irish sovereignty was lost, inadvertently leading to political resentment. The political union also led to a significant slowdown in the Irish economy. In Dublin, mansions of Irish aristocracy were turned into tenement buildings as their owners relocated to London.

One of the most pivotal Irish figures at this time was Daniel O’Connell. Born to a wealthy family in County Kerry, O’Connell was a successful lawyer and an MP from County Clair. He quickly emerged as the leader of Catholic Emancipation. At that time, the “penal laws” prohibited Catholics from various legal rights in Ireland. Even though nine out of ten citizens in Ireland were Catholic, they were barred from holding public offices or marrying Protestants, and many other fundamental rights. One of the most controversial provisions in the penal laws was the Oath of Supremacy, which recognized the British monarch as the supreme governor in all temporal and spiritual matters. This oath did not help ease the religious tension, to say the least.

Internationally, O’Donnell was best known for his antislavery stance and befriending American abolitionist Frederick Douglas. But in Ireland, he is known as the “Liberator.” O'Connell founded the Catholic Organization, one of Europe's most potent mass political movements. Blessed with his great eloquence, he organized large political rallies demanding social changes and political reform. British Prime Minister Arthur Wellesley, an Anglo-Irish Protestant, aided the passage of Catholic Emancipation to head off a potential civil war. Unlike the Irish revolutionaries who came after him, O’Connell believed that the political process, not violent uprisings, was the most effective way to change Ireland.

In 1882, Dubliners constructed a massive commemorative monument to honor his political contribution to Ireland. Two years later, the city proposed to name the city’s main boulevard in his honor. The stately O’Connell Street is a grand edifice of British Dublin and once the city's commercial core. The street has some of Dublin’s grandest civic and commercial buildings. Unfortunately, this postcard-perfect street has been “invaded” by fast-food joints and dollar stores. Despite the city’s best efforts to spruce it up over the decades, O’Connell Street is a shell of its former self. The contrast between relatively low-brow characters and the grandiose architecture is jarring.

What the street lacks in glamour today is more than made up by the plethora of historical monuments. Besides the O’Connell Monument, the most prominent landmark used to be the enormous memorial column dedicated to the legendary British admiral Horatio Nelson. Due to a unique legal arrangement, Nelson’s Pillar remained standing after Ireland gained independence from the United Kingdom. This unabashed British monument was blown up in 1966 by the IRA allegedly. It was not until 2003 that the city finally replaced it with the ultra-modern Spire of Dublin.

At the north end of the boulevard is a memorial to Charles Stewart Parnell, a noted Irish nationalist. He was the leader of the Home Rule League, which advocated for greater autonomy for Ireland without declaring official independence. It was not too dissimilar to the devolution of modern Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Following the Catholic Emancipation, there was an active debate about to what extent the “home rule” was an acceptable solution for Ireland. To Parnell and his political party, home rules may not be perfect, but they are necessary for progression toward ultimate independence.

Known as the “uncrowned king of Ireland,” Parnell is most known for his shrewd and disciplined politics. His Irish Parliamentary Party secured the coveted position as the kingmaker of the hung parliament of 1885. Parnell convinced Prime Minister Gladstone to introduce the Government of Ireland Bill in the following years. Gladstone urged the passage as an act of honor and warned the parliament that home rules may be inevitable due to the sentiment in Ireland. Predictably, the bill was fiercely opposed by the protestant unionists in Ulster. The bill was eventually defeated in the House of Commons.

Ironically, Parnell’s political fortune came to an abrupt end when it was revealed that he had a longstanding adulterous affair with Katharine O'Shea, the wife of a fellow member of parliament. In a deeply conservative Catholic Ireland, the scandal was so explosive and led to Parnell’s political exile. By the moral standards of today, the scandal was certainly overblown. Thankfully, his contribution to Ireland could not be disputed. Nearly a quarter of a million people attended his funeral when hen he passed away at the age of forty-six. The anniversary of his passing, October 6th, is known as “Ivy Day” in Ireland to honor his life.

The most important landmark on O’Donnell Street was the General Post Office (commonly known as the GPO). This grand neoclassical building gained notoriety as the rebel headquarters of the 1916 Easter Uprising. Unlike most other countries, Ireland has multiple “independence days. " This uprising was perhaps the most consequential event of the Irish drive for independence. In 1912, the British Parliament finally passed the Home Rules Bill, but its implementation was put on hold with the outbreak of World War One. While many Irish nationalists volunteered to enlist in the British Army, others thought Ireland should take advantage of the opening when Britain faced external threats. The Irish volunteers arranged to receive arms shipments from Germany, the enemy of Britain.

Much to everyone’s surprise, the uprising was organized by the intellectual elites of Ireland, who had little or no military background. The rebel forces planned to take over seats of British administration, such as Dublin Castle and Four Courts, and established control over central Dublin. The operation did not have a good start due to confusion over the start date of the uprising. However, the British were caught off-guard; many soldiers were off duty at the racetracks outside the city for Easter weekend. After the rebels seized the GPO, one of the rebel leaders, Patrick Pearse, stood outside the front portico and read aloud the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. The proclamation asserts the rightful existence of the Irish Republic and stresses the equality of all Irish citizens regardless of gender. The proclamations were widely distributed in Dublin and other Irish cities.

Although the Irish insurgents took over several landmarks, such as the General Post Office, the British could mobilize quickly to lay siege to the rebels. Due to tactical inexperience and inadequate equipment, the insurgents made several fatal strategic mistakes, including digging a trench at Saint Stephen's Green and failing to cut off vital transportation links into Dublin. Vastly outnumbered and without effective military command, the rebels had little chance of success. The British began to retake rebel positions one by one. The British Navy sailed up River Liffey and bombarded the GPO. Much of the neighborhood along O’Connell Street was flattened.

After days of siege, the rebels inside the GPO ran out of supplies and equipment. Leaders made a daring escape through a side exit at the north of the building. Rebel leaders Patrick Pearse and James James Connolly escaped along Moore Street and set up a new headquarters in a humble apartment building at 17 Moore Street. Patrick Pearse attempted for conditional surrender but was rebuffed by the British commander. On the sixth day, he issued an unconditional surrender, hand-delivered by two nurses, Elizabeth O'Farrell and Julia Grenan, to the British authority. Five of the seven signatories to the Irish Proclamation of Independence surrendered here and were promptly arrested.

Historically, Moore Street is a major shopping street, Dublin’s oldest open-air flower and produce market. Like O’Donnell Street nearby, today’s Moore Street appears run down and somewhat chaotic by Irish standards. Despite its historical significance connected to the Easter Rising, Morre Street received little attention from the city. There are plans to rejuvenate and redevelop the area into a modern shopping complex. The plan was met with fierce opposition from historians and descendants of Irish revolutionaries. Some even call Moore Street the “Alamo of Ireland.” Save Moore Street Committee, a civic group, successfully lobbied against Nos.14-17 Moore Street’s demolition and continuously advocated for the preservation effort.

Other than a plaque affixed by an upper window at 17 Moore Street, there are very few traces of the event that unfolded in 1916. One unexpected find was an enormous plaque mounted above a garage door on a small side street. This plaque commemorates Michael Joseph O'Rahilly, a founding member of the Irish Volunteers organization and responsible for arming the military. Ironically, he opposed the uprising as he could not see how the volunteers could overcome the British and be successful. When the rebellion was announced, he joined in regardless. He was severely wounded by the machine guns but managed to crawl to an adjacent building. With gunfire all around him, he slowly bled to death for the next nineteen hours. He left a note for his wife in his dying hours:

“Written after I was shot. Darling Nancy, I was shot leading a rush up Moore Street and took refuge in a doorway. While I was there I heard the men pointing out where I was and made a bolt for the laneway I am in now. I got more [than] one bullet, I think. Tons and tons of love, dearie, to you and the boys and to Nell and Anna. It was a good fight, anyhow. Please deliver this to Nannie O'Rahilly, 40 Herbert Park, Dublin. Goodbye, Darling.”

His slow and agonizing death became a well-known tale of the physical pain of the uprising. The six-day uprising resulted in large-scale destruction in central Dublin. Most Dubliners were not supportive of the insurrection. The conflict decimated the city physically and brought economic and political uncertainty to the otherwise prosperous city. There was large-scale looting of businesses amid all the chaos. When Patrick Pearse read aloud the proclamation in front of the GPO, there was no cheering crowd. Over half of the casualties were civilians, primarily a result of the artillery shelling by the British forces.

Most Dubliners were shellshocked by the Easter Rising. Even some sympathetic Irish republicans were dismayed by the poor planning and the civilian casualty. Historians often muse how different the insurrection may have been if it had not been for the delayed start. The failed uprising also wiped out a whole generation of the republican leadership. Most prisoners taken in the aftermath were taken to Kilmainham Gaol, the massive prison on Dublin’s outskirts.

Kilmainham Gaol was initially a reformed correctional facility with adequate ventilation and private cells. However, it quickly became overcrowded and dilapidated. It was used as a holding facility before prisoners were transported to the penal colonies in Australia. Overcrowding became especially acute during the Great Famine, when many Irish peasants were imprisoned for begging in Dublin. Because the government was mandated to feed all prisoners, many would actively commit crimes to be in jail. It was better to be incarcerated than starved to death.

Today, Kilmainham Goal is most celebrated for its role in Ireland's independence movement. It was so popular with the public that we had to make advanced reservations weeks ahead. I was suspicious about how enjoyable a visit to the city jail could be. Their hour-long guided tours were the only way to visit, and it was clear that most visitors in our group were Irish and treated the place as a sacred ground. Based on all the questions people asked during the tour, everyone except us is well versed in Irish history.

Kilmainham Goal ceased to be a jail in 1924 and was substantively abandoned for decades. Much of the Victorian-era cells were partially restored to give us a glimpse of the living conditions. To reduce the risk of airborne illness, there is excellent ventilation. But I could also imagine how cold and damp it could be in the depth of winter. At its height, as many as five prisoners shared the same small cell, and there was no segregation by gender or age. The rations were poor; the only heat source was a candle every two weeks.

After the failed Easter Rising, nearly all insurgent leaders were imprisoned in Kilmainham Goal. One of the most tragic stories here was that of Joseph Plunkett. Joseph Plunkett was one of the signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic and was responsible for planning the insurrection. He fell significantly ill just days before the operation and was too sick to participate in active combat. However, he managed to join his comrade at the GPO for the rising. He was taken to Kilmainham Gaol like the rest of the leaders. When his fiance Grace Gifford learned that Plunkett was sentenced to be executed by the firing squad, she rushed to a jeweler and the jail to convince the guards to let them get married.

Thanks partly to the advocacy of the priest, the two were able to wed in the prison chapel just a few hours before the execution. The chapel was faithfully restored to how it appeared in Plunketts’ time. The newlyweds only had ten minutes together, and Joseph was executed only a few hours afterward. It was a classic tragic love story. Grace was arrested and jailed here during the Irish Civil War in 1923. A noted artist and cartoonist, she decorated her cell with an image of Madonna and the Christ Child. The recreation of Kilmainham Madonna now graces the back wall of her cell. It may not be the most beautiful artwork, but it certainly brightens up the drab environment.

One of the most important areas of the jail was a narrow wing where all the leaders of Easter Rising were held, colloquially called “Informers Corridor.” Their names are proudly displayed above the cell, and it was a who and who of Irish revolutionaries. I could only imagine what this place meant for most Irish citizens. But architecturally speaking, the most interesting space is the 1857 Victorian addition. Among the noted inmates jailed here included Éamon de Valera, the third President of Ireland. It employs the popular “panopticon” design focusing on efficient surveillance. More importantly, the large central atrium provides much-needed natural light for inmates. It inadvertently became the most photographed space in the entire complex.

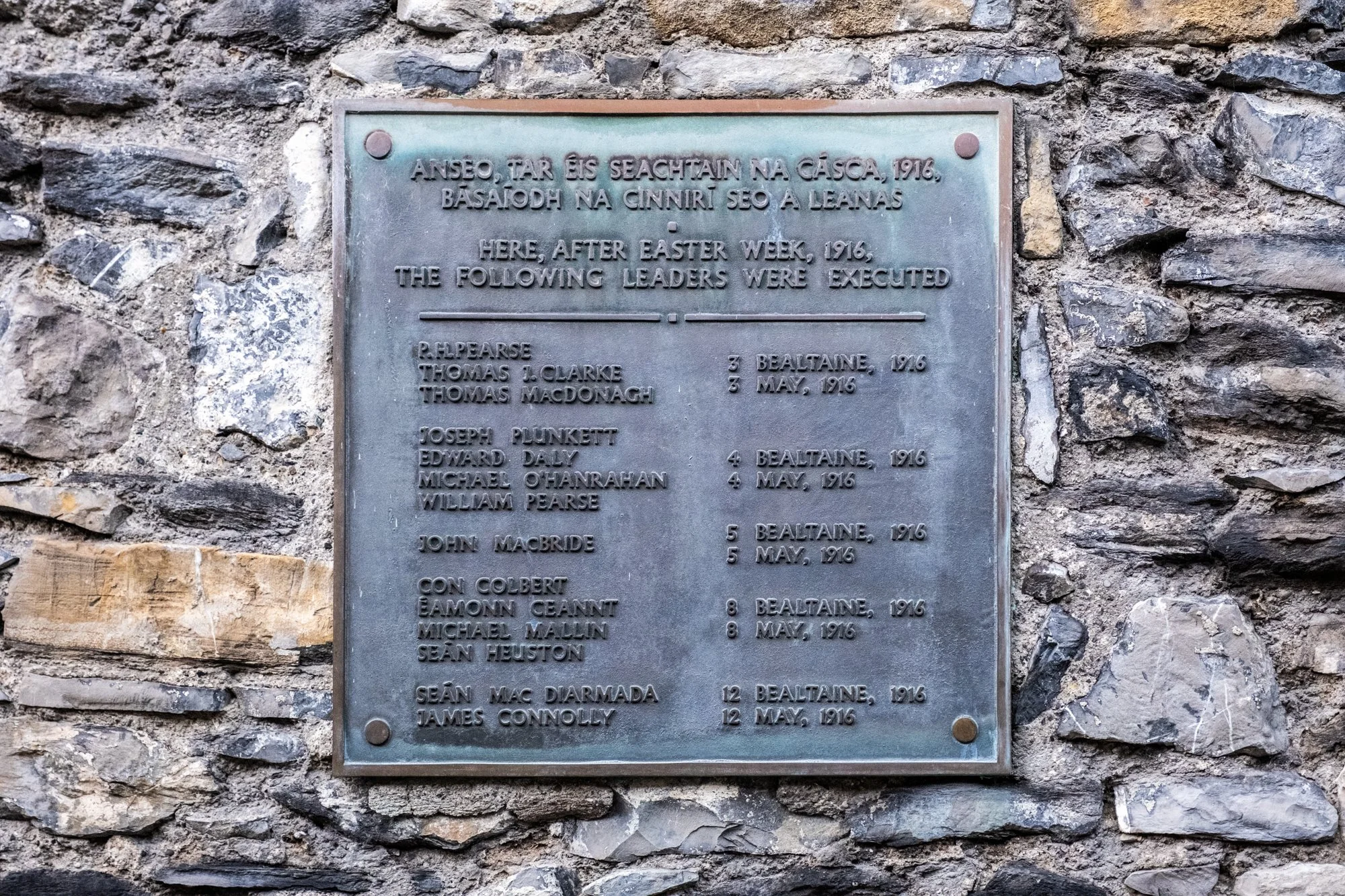

However, the most historically significant space in Kilmainham Gaol is the Stone Breaker’s Yard. As the name implies, this enclosed courtyard was used for stone breaking. Because of the noise of stone breaking, this was also the most “isolated” section of the entire prison complex. For this reason, the courtyard was also the preferred place of execution. One hundred eighty-seven people were tried for Easter Rising, most in secrecy, without proper legal defense. In the end, ninety of them received death sentences. Over ten days, fifteen leaders were executed by firing squads, including all seven signatories of the Proclamation.

After the Easter Rising, London appointed Sir John Maxwell Commander-in-Chief of Ireland and declared martial law on the island. Hoping to prevent future rebellions, Maxwell was determined to exert maximum punishment on the rebellion leaders by suspending proper due process in the court marshall. The expediency and secrecy surrounding the execution prompted an outpouring of sympathy from the public. The most gruesome execution here was that of James Connolly, the great populist trade union leader. He was severely wounded during the insurrection and thought to be terminally ill at the time of his trial. According to British custom, mortally injured should have the dignity to die on their own. However, Maxwell was determined to make an example out of him. Connolly was brought to the stone breaker’s yard in an ambiance from the hospital and strapped to a chair in front of the firing squat.

The disrespect of Connelly’s execution quickly spread. Many even believed he was already dead before arriving at Kilmainham Gaol. He was the last leader to be executed. The rise of anti-Britain sentiment alarmed British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith and forced Maxwell to commute the remaining death sentence to hard labor. It was said that it was the execution of the rebel leaders, not the Easter Rising, that prompted the public to support formal independence from the United Kingdom. Today, a small black cross marked the spot of his execution. One could argue this is one of the most sacred spots in all of Ireland. The solemn atmosphere of the yard was chilling. Even as a foreigner, I could feel the weight of this place.

At the end of the guided tour, there is a small museum with comprehensive exhibits on the history and life inside Kilmainham Gaol. I wish I had read more about the Easter Rising before our visit or watched the 2016 five-part series Rebellion. The visit reminded me just how little I knew about Irish history. Considering how prosperous today’s Ireland is, it was mad to think it was just a colony until 1941. As much as Easter Rising was lionized in the modern history of Ireland, it was simply an epoch of the long march toward formal independence. After the Easter Rising, the political party Sinn Féin took on the mental of Irish republicanism and became a dominant force in Ireland. However, there was not a united front on the best path forward.

Just three years after the failed Easter Rising, the Irish War of Independence broke out against the British. In 1918, Sinn Féin won an overwhelming landslide in the parliamentary election and subsequently organized a separatist government. They declared independence from the United Kingdom and officially adopted the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, first read aloud by Patrick Pearse in front of the General Post Office in 1916. The two-and-a-half-year guerrilla war pitted the Irish Republican Army (IRA) against the British Army and affiliated volunteer forces of the Ulster Unionists.

One noticeable event during the War of Independence took place in Dublin at the Custom House on the north bank of the River Liffey. The imposing neoclassical edifice symbolized British Ireland and was a major center of the British administration in Ireland. It was a natural target. The rebellion was the most significant in Dublin since the Easter Rising. The IRA managed to burn the building’s contents, but the operation also resulted in the most serious casualties. An exhibit inside the Custom House Visitor Center is dedicated to the bloody episode. Coincidentally, just to the west of the Custom House is the original Liberty Hall, the rebel headquarters of the Irish Citizen Army during the Easter Rising. While the original building is now rebuilt as a modern office tower, it now towers over the Custom House, a symbolic triumph over British Ireland.

Our last stop in Dublin was the Garden of Remembrance. Located at Parnell Square north of O’Connell Street, this solemn garden commemorates all who perished for Irish freedom. The list of uprisings and wars it commemorated was long and speaks to the country’s long struggle for self-determination. The garden marked the spot where many of the leaders of the Easter Rising were held before being transferred to Kilmainham Gaol. The place was inaugurated for the Semicentennial of the Easter Rising. It is filled with numerous mosaics and sculptures, including a statue of the Children of Lir by Oisín Kelly. The Art Deco style may seem very period-specific, but the sunken garden is a tranquil oasis befitting the memory of those who made the ultimate sacrifice.

During Queen Elizabeth II’s historic state visit to Ireland in 2011, she elected to visit the Garden of Remembrance. As the first sitting British monarch to visit Ireland since its independence, her visit was celebrated in the Irish press as a graceful reconciliation between the two nations. I think this was a befitting terminus of the trail of the Irish Revolution through Dublin. We left Dublin with a deep appreciation for Ireland and those who fought and died for freedom.