Salk Institute - An American Masterpiece

As a practicing architect, I often encountered two questions: “Who is your favorite architect, and what is your favorite piece of architecture?” For many of my fellow architects, their answers inevitably evolved around one of the three towering figures of modern architecture: Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Llyod Wright. Some might also mention contemporary architects such as Rem Koolhaas, Peter Zumthor, Herzog, and de Meuron. The answer is simple: it is the American architect Louis Kahn and his Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California.

Born in the seaside town of Pärnu and grew up on the island of Saaremaa (both within the border of the Republic of Estonia today), Louis Kahn emigrated to the United States at a very young age and settled in Philadelphia. A course he took during his senior year at Philadelphia Central High School set him toward architecture. His career dramatically turned after a residency at the American Academy in Rome. More than any true modern architect, Kahn incorporated elements of ancient architecture while stripping away classical ornaments. His vision for modern architecture is rooted in the three Vitruvius ideals of classical architecture: firmitas (strength), utilitas (utility), and venustas (beauty).

Kahn’s career was short but productive. He produced an impressive array of projects, ranging from private houses in suburban to an enormous capital complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Five of his projects were awarded the prestigious Twenty-five Year Award, one of the most prestigious architectural designations, by the American Institute of Architects (AIA). Of all of his works, the Salk Institute is often lauded as his finest work.

In 1959, Jonas Salk, the scientist behind the polio vaccine, decided to use the proceeds from the vaccine to found an institute of biological research. A track of land along the cliff of La Jolla was gifted to Salk by the city of San Diego. As one of the most preeminent scientists and with financial resources, Salk envisioned attracting the world’s best scientific mind with the most architecturally magnificent research center ever constructed. He famously told Louis Kahn that he wanted a laboratory worthy of a visit by Pablo Picasso.

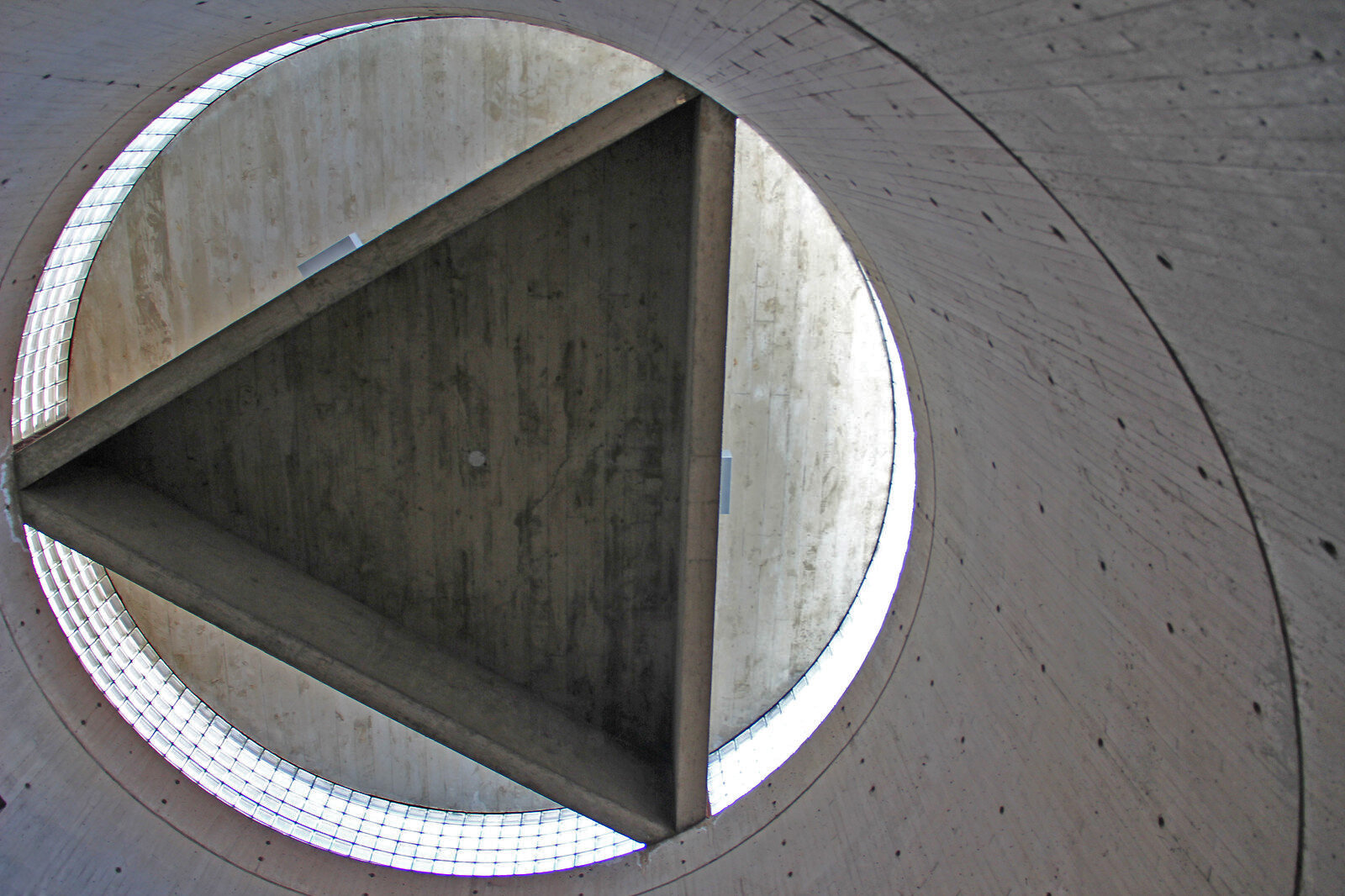

The campus we see today is a masterpiece of modern architecture. The main laboratory spaces are supported by story-high reinforced concrete truss, which accommodates building systems and utilities for open and flexible laboratory space. Adjacent to the laboratory space are private offices for individual senior researchers. Each thirty-six individual office faces the central courtyard and is afforded an unparalleled view of the Pacific Ocean. The specially angled concrete wall allows the uninterrupted ocean view and the sightline down to the courtyard below.

A central courtyard organizes the campus complex. It was said that Louis Khan consulted extensively with the noted Mexican architect Luis Barragán on the design of this plaza. At Barragán’s advice, the courtyard is lined with travertine and ‘featureless’ except for a thin channel of water that bisects the courtyard and draws your eyes toward the horizon beyond. The architectural and landscape design principles may suggest it is an unpleasant public space. But instead, it is one of the most magical and spiritual spaces in the United States.

The whole campus comprised five different materials: travertine, reinforced concrete, teak, stainless steel, and glass. Each of these materials expresses a timeless quality that is the essence of Kahn’s artistic vision. The best summary I have ever read was provided by American architect I.M. Pei:

“Architecture has to have an element of time. How can you judge a work today, let’s say a work by anyone one of these modern architects that you know that is exciting and wonderful? And then what will happen to it twenty, fifty years later? That’s the measure. That is why that Salk Center will always be as perfect as it was conceived. The teak wood may fade away ... probably did, or has ... but the spirituality of that project will remain. Now that building will with stand the test of time, no question about it.” ”

This sense of permanence made works like Salk Institute so poignant in the modern world. This quality is particularly poignant nowadays, where even architecture is now considered disposable, such as those of national pavilions at any world exposition. A building’s physical and artistic longevity is the true mark of its greatness. Opening up any architectural publication today, buildings today are about following the trend. And in this age of green architecture, isn’t Kahn’s vision of timelessness and monumentality an ultimate expression of suitability?

On a personal note, I have always had a deep emotional connection to the Salk Institute. My sister attended the nearby University of California in San Diego (UCSD). During the few years she lived in La Jolla, our family tradition was to make the 8-hour drive from San Jose to spend Christmas and New Year in Southern California. Although San Diego and La Jolla are perfectly idyllic, my favorite memory every year was visiting the Salk Institute.

I have spent countless late afternoons here watching the sunset and enjoying how the light hit the bare concrete. There was just a sense of sheer serenity and mysticism. Much seemed to have changed since my last visit in 2012. Perhaps due to over-tourism or security concerns, the central courtyard of the Salk Institute has been restricted to its employees. Gone was the day when we could stroll over the central courtyard for a quiet, contemplative moment in solitude. The only way to visit was through the official docent-led guided tour.

Following the successful inscription of eight architectural works of Frank Lloyd Wright on the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 2019, I do think it is time for the United States to place many of Kahn’s works on the tentative list for future inscriptions. In my opinion, below are six other works of Kahn that could be collectively considered for nomination:

Yale Center for British Arts, New Haven (CT)

Phillips Exeter Academy Library, Exeter (NH)

Trenton Bath House, Trenton (NJ)

Jatiyo Sangshad Bhaban, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Kimball Art Museum, Fort Worth (TX)

Norman Fisher House, Hatboro (PA)

Fortunately, most of his best-known works are institutional in nature and remain accessible to the public. Of all his significant works, I could say every single one of them that I have visited taught me something about architecture. Each building, no matter what function, became a beautiful meditative space. Indeed, his capitol building in Dhaka alone prompts me to place Bangladesh on my travel bucket list.

For anyone who likes to explore more works of Louis Kahn, the 2003 documentary movie My Architect is one of the best biographical movies ever made about an architect. Produced by hi son Nathaniel Kahn, this film not only revisited many of Louis Kahn’s best works (including the Salk Institute) but also took an intimate look at the troubled personal life of the architect. The film is both educational and touching.